By Sarah Stevens

As we near the end of the semester, we also draw closer to the ever-approaching shadow of finals week: the final, exhausting burst of effort to conclude an entire semester’s worth of writing. At this point, you’re probably itching to cut a few corners, maybe by skipping that final once-over or the single peer review that you couldn’t get to on time. As a harried English major, I totally get it—but no matter how slammed I am for time, there’s one stage of my writing process that I never skip, and that’s pre-writing.

I divide my pre-writing stage into four simple steps: finding resources, making annotations, outlining my major points, and drafting a thesis statement. After a lot of trial and error, I have come to realize that following this process not only makes me feel better about my productivity, but that it also cuts down on the effort and stress that I experience towards the end of a project. Here’s how it works:

1. Finding Resources

Before I come up with any kind of argument or thesis statement, my first step is to pick a general topic and read up on what other scholars have to say about it. Want to write about gender dynamics in Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, for example? Pop over to the WKU Libraries website to find a few articles that strike a chord. Not sure what you want to write about at all? There are several paths you can take to finding that jumping off point—you can drop by your professor’s office hours to ask for help generating ideas, or you can even pop some keywords from your writing prompt into Google to see what people think outside of academia. If you’re still having trouble, check out our Brainstorming category on the Writing Center Blog—we have more posts about beginning research, finding a topic, and getting started on papers.

Why it Helps: There’s nothing worse than getting halfway through a draft and then realizing that you can’t find enough resources to support your argument. Doing preliminary research keeps you from going all the way back to the drawing board.

2. Making Annotations

Now that you have your resources, your next step is to turn all of that new information into usable materials for your essay. You can do this quickly and easily by making annotations—a fancy way of saying that you write all over those resources that you just found. Even if the word “annotations” sounds intimidating, the actual process is easy: take a highlighter, pen, or pencil and underline the passages that stand out to you. Were they interesting? Do you disagree with them? Do they remind you of something that you talked about in class? Do they sound like they could be used to support your argument? If you answer yes to any of these questions, mark those places on your resources (or on the original text that you’re analyzing, if applicable). As you go, make some additional notes in the margins of the text that tell Future You why that part is important. If you don’t want to use words, you can come up with a system of symbols — stars can be supporting evidence and exclamation points can be statements you disagree with, for example.

Why it Helps: All of these marks on your papers serve a dual purpose: first, they make it easier to find passages later, and second, they make up the very beginnings of your argument. Once you start drafting your paper, it’s easy to glance back at your annotations and know exactly what evidence to use and what you want to say about it. Also, no more frantically flipping pages trying to find that one specific quote you need!

3. Outlining Major Points

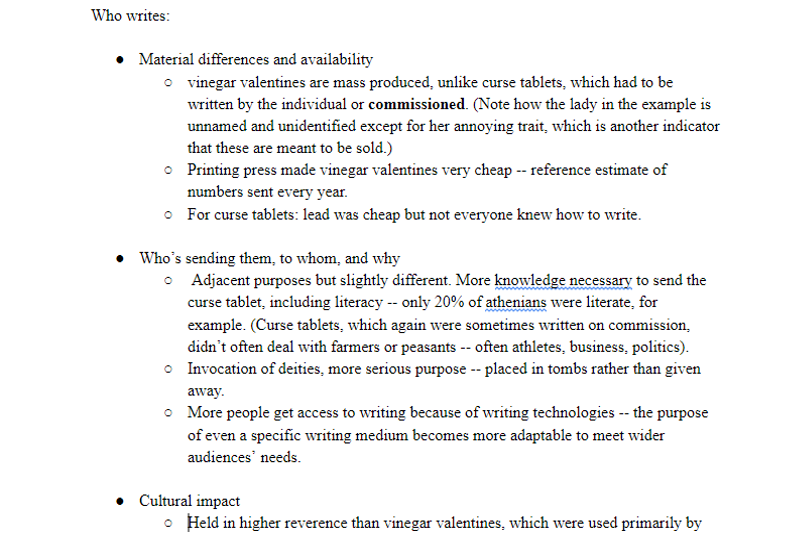

After I have a general idea of the resources that I’ll use and the point that I want to make, my next step is fitting my argument into a logical pattern that I can follow when drafting my essay. Depending on the project, I do this either on paper or in a separate digital document that I keep close by for easy reference. Give yourself permission to be messy here—in an outline, grammar isn’t important, and neither is essay formatting. My personal preference is to have a stacked, bulleted list of main points in the order that I want to talk about them, like so:

In my example, each major topic has a short list of supporting evidence beneath it, with every point representing a paragraph or two that I wanted to write in my essay. No matter how you format your outline, the point of this step is that you begin to form an argument that flows and progresses logically from introduction to conclusion.

Why it Helps: When writing an essay, your outline is like a lighthouse: it keeps your argument from drowning in details or veering off course. Also, it helps you meet the intimidating word or page count that your professor slipped into the guidelines. If you already have a list of things to talk about, you’re much less likely to peter out in the middle of the project.

4. Drafting a Thesis Statement

The last stage of my pre-writing process is drafting a working thesis statement to add to the top of my outline. After doing preliminary research and creating an outline for your argument, most of the work for this part is already done. The goal here is to condense what you’re trying to say into a sentence or two, hitting a couple of main points and making a definite statement about your beliefs on your topic. It’s important to note that while the thesis does function as a guiding statement for your essay, it doesn’t have to be concrete: if your writing takes a different direction than you were expecting in the beginning, it’s okay to go back and modify your thesis to match your new conclusions.

Why it Helps: Even though your thesis statement doesn’t need to be set in stone, it serves as a convenient summary of your outline for you to keep in mind while you write. Most writing projects require some kind of thesis statement anyway, and it could save you some summary work later; you won’t have to retrace your logic in order to distil it.

Of course, even though these steps work for me, everyone’s writing process will be different. I encourage altering or reordering these steps to fit your preference — and of course, we in the Writing Center can help you brainstorm your essays or your process along the way.